Exposing the Plight of the Poor

Charles John Huffam Dickens (1812-1870), English writer and social critic, creator of some of the world’s best known fictional characters, is considered by many to be the greatest novelist of the Victorian era, his novels and short stories continuing to be widely read.

Born in Portsmouth, to a middle-class family; at the age of 12, with his father committed to a debtor’s prison, Charles was forced to pawn his book collection, leave school and work in a dirty, rat-infested, shoe-blacking factory. Three years later he returned to school and then began his literary career as a journalist.

Dickens is credited with editing a weekly journal for 20 years, authoring 15 novels, five novellas, and hundreds of short stories and non-fiction articles, and many letters. By 1842, well established as an author, Charles began publishing Martin Chuzzlewit, a monthly serial, but with low sales and with publishers threatening to reduce his monthly income, financial problems ensued.

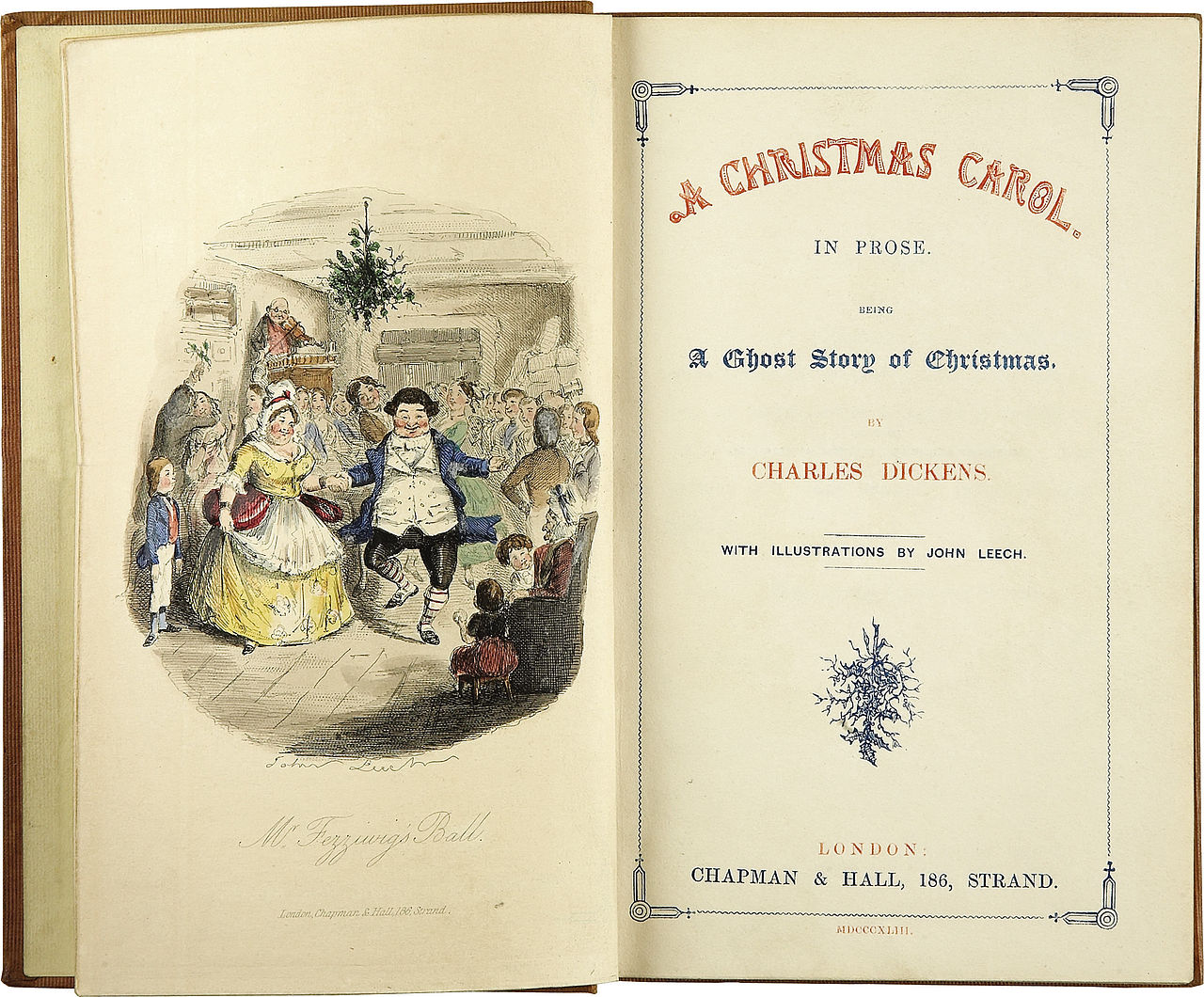

In return, Dickens paid to publish A Christmas Carol himself, taking a percentage of the profits. Many problems ensued including unacceptable endpapers and binding material. 6,000 copies sold quickly and second and third editions released before the end of 1843. However, the high production costs insisted on by Dickens led to disappointing profits.

A Christmas Carol

A Ghost Story of Christmas, known as A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens, first published in London on December 19, 1843 and illustrated by John Leech, was completed in six weeks, the final pages being written in early December. Appearing just in time for Christmas, the book was immediately popular. Charles worked out most of the tale while taking 15 to 20 mile walks at night around London.

In this Victorian era, Christmas season celebrations were growing in popularity and many things we now consider “Christmassy” were just coming into vogue. The Christmas tree and its use, introduced to Britain during the 18th century, was now popularized and championed by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at the royal court. The tradition of sending Christmas cards began the same year that A Christmas Carol was published. Combined with a renewed interest in Christmas carols, family gatherings were popularized with seasonal food, drink, games, dancing and generosity of spirit.

Dickens expertly captures the mood of the times, while reminding us of the less fortunate, personified through Ebenezer Scrooge whose transformation is the central focus of the story. Described as “a protean figure always in process of reformation,” we see him replace focusing on wealth, to caring and sharing for the less fortunate, improving Bob Cratchit’s financial situation and becoming a friend to the family, thus illustrating Dickens’ belief that all of society, the rich and poor, should communicate and work together so that all will benefit.

Writing about Christmas was not new to Dickens, having written several stories previously featuring mean-spirited people who reform, through visits by goblins showing the past and future. The treatment of the poor and the ability of a selfish man to redeem himself by transforming into a more sympathetic character are key themes of the stories.

Here is a short recap of the well-known novella, A Christmas Carol, which is divided into five chapters or “staves.” In the first stave, on Christ Eve, miserly Ebenezer Scrooge receives a visit from his deceased business partner, Jacob Marley.

The second stave covers the Ghost of Christmas Past, reminding Scrooge of his lonely childhood and kindness shown by others. Thirdly, the Ghost of Christmas Present shows the Cratchits in poverty with the youngest, Tiny Tim severely ill. Next, by the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, Scrooge witnesses his own funeral and those who are happy he is dead. Witnessing Tiny Tim’s death prompts Ebenezer to make a vow to change his ways. In the fifth and final scene we find a changed man waking up Christmas morning, sending a large turkey to feed the Cratchets, giving Bob a pay raise and treating all with kindness and generosity.

A Christmas Carol, the most successful book of the 1843 holiday season, received mostly favorable reviews and Dickens went on to write four other Christmas stories. In 1849, Charles began public readings which proved so successful, he performed 127 times until his death in 1870. A Christmas Carol has never been out of print, translated into several languages, and continues to be just as popular today.

Compassion for the Poor

Dickens wished to expose Victorian society; the rich enjoying comfort and feasting at Christmastime, while children were forced to live in poverty and dreadful conditions in workhouse.

Influenced by his experiences and touched by the conditions of poor children, Dickens toured the Cornish tin mines. Angered at seeing children in appalling conditions, Charles’ passion for the suffering was reinforced while visiting a London school for educating the half-starved, illiterate street children.

In 1843, a report exposing the effects of the Industrial Revolution upon working class children horrified Dickens, who at first planned to publish a pamphlet to appeal to the people of England on behalf of the poor man’s child. Changing his mind, he wrote, “You will certainly feel that a sledge hammer has come down with twenty times the force—twenty thousand times the force—I could exert by following out my first idea.”

Later that year, in a speech, urging workers and employers to begin reforms, he began to realize writing a “deeply felt Christmas narrative” would be the most effective way to touch a broad segment of the people with his deeply felt social concerns about poverty and injustice. And thus, we have a most unforgettable classic tale

A Christmas Carol: Analysis

A Christmas Carol is fully ingrained in our culture as an archetypal story; the value of helping those in need, and dramatically illustrating personal redemption. In exposing the plight of the poor, Dickens’ exposes the dangers of placing too much faith in money rather than in our fellow human beings.

The story can be seen as a social commentary dramatizing conditions of the poor. Dickens, facing horrible poverty in his childhood, knew well the plight of this segment of the population which continues to this day.

Pay attention to the images of fire and brightness, symbols of emotional warmth, happiness and understanding. Notice how this changes in Scrooge’s life, and at the end, he instructs Bob to “Make up the fires.”

Scrooge takes on the role of father figure to Tiny Tim, symbolizing that the children of the poor are the responsibility of all, and if their own parents cannot provide for them, generosity from the well-off is required.

A debate as to whether this a fully secular story or a Christian allegory continues with quotes such as Dickens story is a “secular vision of this sacred holiday,” and through its mythic qualities, the gospel-like novella allegorically captures the Christian concept of redemption, “even the worst of sinners may repent and become a good man.”

The message to mostly middle-class readers, urging compassion for poverty that afflicted millions of their fellow Britons, is just as poignant today. “Scrooge” and “Bah! Humbug” are known to people all over the world, whether they have read A Christmas Carol, or experienced one of the countless theatre, film, or tv, adaptations.

So I say, re-experience this classic Christmas tale, and say with Tiny Tim, “God bless us, everyone.”

[In her retirement, CJ Austin continues to read, write, publish and share insights from her professional background (marriage and family therapy) with others. Contact: cjaustinauthor@gmail.com]